“I Had Another Chance:” Michigan Transplant Recipient Spreads Minority Donor Awareness

Jake Newby

| 5 min read

Jake Newby is a brand journalist for Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan.

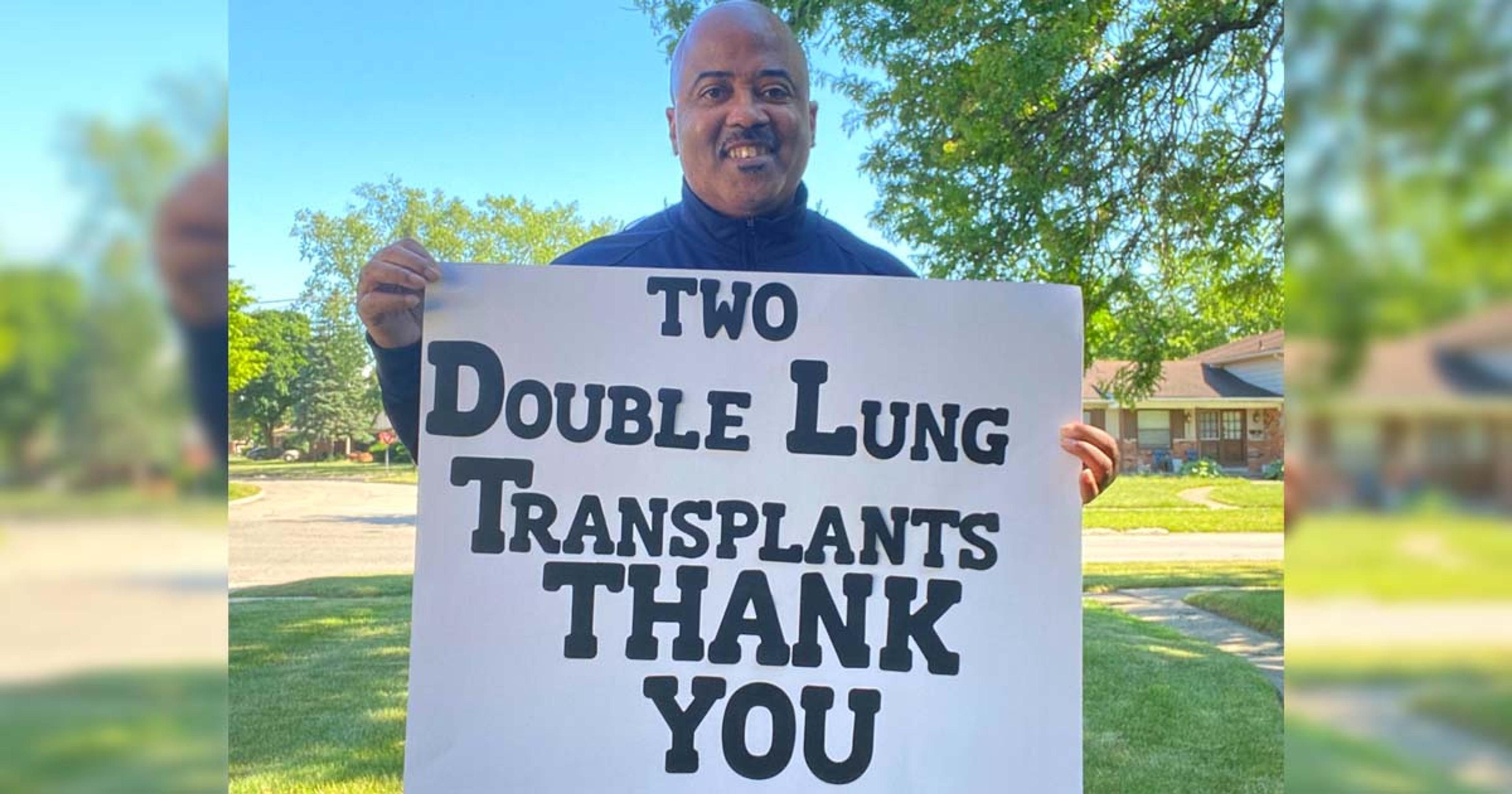

When Southfield, Michigan resident Michael Love woke up from his first double lung transplant in 2015, the first thing he did was reach for his nasal cannula, a tube used to deliver supplemental oxygen. As Love slowly realized he was breathing on his own for the first time in a long time, he broke down in tears. “It was so overwhelming for me that I just started crying,” Love said, during a phone interview with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM). “To say it was a game-changer is an understatement. Because I felt good, I felt like I was ready to get up, run out of the hospital and pick up where I left off.” Love’s euphoric feeling was unfortunately short-lived. After two years of suffering from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Love thought he was on the fast track to recovery after his transplant. But less than three years later in early 2018, he learned his lung transplant had ultimately failed. “I had double pneumonia. I couldn’t even walk at one point. My transplanted lungs went into chronic rejection,” Love said. “So, at that point, I was told that I would have to do the transplant again.” Devastated at first, Love matched with another donor and was penciled in for a second double lung transplant in the fall of 2018. “My blessing in this was that I had another chance,” said 57-year-old Love during the interview. “That chronic rejection was not it for me.” Despite numerous complications and a 43-day hospital stay following his second transplant surgery, Love remained positive and found perspective in the process. “I got to know people in the hospital that were there for months and months, so to just be there a month and a half? I was blessed for that,” he said.

Educating others and spreading MINORITY DONOR awareness

Love, a BCBSM member, retired from his longtime pipe fitting career as he recovered from his second transplant. Once he got to a place where he felt mostly healthy, Love took up public speaking and education. He wants to teach others how significant organ donation is. “Because I was blessed with two transplants – not that I went into this wanting two, but that’s how things happened for me – I try to show people, ‘Hey, I’m here because somebody gave,’” Love said. “And I try to make other people think about that.” Love became a Transplant Living Community (TLC) volunteer at Henry Ford Hospital in 2019, where he spends time visiting organ recipients after their transplants. He said he coaches them through the post-transplant experience, which can be mentally and physically exhausting. “I also teach classes for people that are trying to get listed,” he said. “There, I let them know what is expected of you as a transplant recipient. The things that you can do, the things that you can’t do. And then, I feel like part of my role is to be a motivator. Because it’s rough to go through this.” Love also works with Gift of Life Michigan, the state’s federally designated organ and tissue recovery program, to advocate for organ donation.

On behalf of both Gift of Life and the Detroit Minority Organ Tissue Transplant Education Program (MOTTEP) Foundation, Love has seized the opportunity to spread minority donor awareness. A Black man himself, Love said he understands how organ donation can be a delicate subject in the Black community. But he points to himself as proof that the organ donation registry saves lives, no matter a person’s race, creed, or color. “When it comes to medical things, a lot of us are skeptical. Simply because of things that have happened to Black people in the past,” Love explained. “As you grow up, a lot of the information you get is from your family members. And because you love and trust them, you figure that what they’re saying to you is gold. And I get it, African Americans have been subjected to a lot of terrible things in the past, and it can make you skeptical about some medical things.” Love said it’s crucial that more minorities register for organ donation based on the compatibility factor. As of 2020, 16.4% of Black people were living donors compared to 33.4% of white donors, according to the United States Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. “As an African American, I can take any organ from anybody’s nationality, but sometimes because of genetics, if another African American donated and it was compatible with me, that transplant might work a little bit better,” he explained. “It’s not to say that I couldn’t take an organ from anybody else. But genetically, sometimes it helps.” Love takes every opportunity he can to support Gift of Life and MOTTEP, because organ donation saved his life – twice. He said he doesn’t know the family members of the organ donors who saved his life, but he’s researching that now. In the meantime, he’s healthy, grateful, and eager to continue working to increase the number of registered donors. “Organ donation is extremely important,” he said. “It’s something that needs to be discussed with your family and your friends. Go to (the Gift of Life) website and register. It’s hard for me to even put this into words, but for me, I feel like I’m a walking advertisement for organ donation. Like, ‘Hey, look at me. I wouldn’t be here if someone else didn’t sign up.’” You can learn more about donation or register to become a donor on the Gift of Life Michigan website. Read about other Michigan residents persevering through health scares: ‘Strong-Willed’ Michigan Teen Battles Back from Multiple Open-Heart Surgeries Detroit R&B Artist Shines Despite Rare Case of Multiple Sclerosis Exercise After COVID: Michigan Runner Races Again After ‘Severe’ Bout with Virus Photo credit: Michael Love