Older Gay Adult Credits Detroit Hannan Center’s Inclusive Mental Health Services, Intergenerational Community Programs with Helping Him Through Personal Struggles

Jake Newby

| 5 min read

Detroit resident Atiba Seitu was “lost” and “discombobulated” in April 2023 when his uncle transitioned to end-of-life care. Seitu knew he needed counseling, but he didn’t know where to turn. As an openly gay man in his mid-60s, he struggled to connect with counselors before and was apprehensive about piddling through that process again.

“I always said, since I’m gay I prefer to have a gay therapist,” Seitu said, during an interview with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM). “I just always feel like a gay person can relate to our issues a little bit better. What we’re going through, you can kind of be a little bit open. And they kind of know the experience, I think that’s important.”

What Seitu described was culturally congruent mental health care, a concept in which a person’s clinician or counselor shares the same ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation or has similar life experiences as their client.

Mired in one of the lowest points of his life, Detroit’s Hannan Center helped facilitate culturally congruent counseling for Seitu. The Hannan Center serves senior adults in southeast Michigan with classes and workshops and day programming for individuals with dementia and social work, including case management and mental health.

In February, a group of eight philanthropic partners in the city that includes BCBSM and the BCBSM Foundation targeted funding to seven Detroit-based, Black-led community-based organizations through an innovative pilot program. The Hannan Center received funding and used its grant to connect LGBTQIA+ adults like Seitu to mental and physical health care services.

“There’s a familiarity when you’re talking about having services offered by people to people that they’re in the same community with,” said Melissa Draughn, director of social work at the Hannan Center. “I think there’s always that level of trust that comes from people of the same culture.”

After a member of Seitu’s uncle’s church mentioned Hannan Center services to Seitu last spring, he promptly filled out an application and was connected to a counselor – a man, named Dan – who Seitu met regularly for one month. Late in 2023, the Hannan Center transferred Seitu as a patient to another counselor, a woman named Melissa. Seitu met with her regularly until recently and still connects with her here and there when he’s struggling.

Seitu said the two Hannan Center counselors taught him some helpful techniques to calm his anxiety.

“One thing I started to do was center myself, sit down and find something on the wall – a painting or an object – and just focus on that,” Seitu said. “That really worked a lot. If I had some anxiety, I’d go on the back porch and look at the flowers or something like that and focus on that. Nothing else. To quiet my mind down. Then I’d step back and reassess my issue like, “is it something I can take care of right now? Is there something I can control right now?” and go from there.”

If there was one bit of advice or guidance that Seitu took from his Hannan Center therapy sessions, it was the following words of wisdom:

“Comparison is the killer of joy,” Seitu said, of the advice Melissa gave him. “That was gold to me. If you compare yourself to other people you’re never going to measure up. I’d talk to her about some of my art sometimes and I’d be kind of down and she’d say, ‘Atiba, you can’t compare yourselves to what other people are doing.’ It was easy to talk to both of them, her and Dan.”

How Hannan Center programming helped Seitu make meaningful connections

The calming techniques and counseling sessions weren’t the only services Seitu benefitted from since being referred to the Hannan Center more than a year ago. He said he also got great joy and fulfillment from the Center’s recent Requiem Project, an intergenerational collaborative program between the Hannan Center and the Detroit School of Performing Arts that featured conversation among students and elders. The project included classes and exercises between December until April, culminating in an art exhibit in May.

Weeks of classes and exercises allowed the age groups to examine Detroit’s rich history and culture through each other’s lenses and perspectives.

“Being referred to another program within that center was really good for me,” Seitu said. “I went to (the exhibit) and it was amazing. I was really impressed.”

Seitu said he held those intergenerational connections close to his heart. He’d like to be involved in more programs that capture the spirit of the Requiem Project.

“We don’t really get a lot of opportunities to do that in society; we separate ourselves,” Seitu said. “My takeaway from (the project) is how important it is to not separate elders from young people in our culture. We kind of create a fissure between the age groups where it’s like, ‘you’re old, I’m young and we got nothing in common.’ Well, a lot of the students here were really talkative, they asked questions, they got into it. It was really refreshing. I think it’s good for our souls, for our minds to interface with young people, and I felt like the same was true the other way around.”

Learn more about the Hannan Center’s social work initiatives centered around older adults by visiting this link.

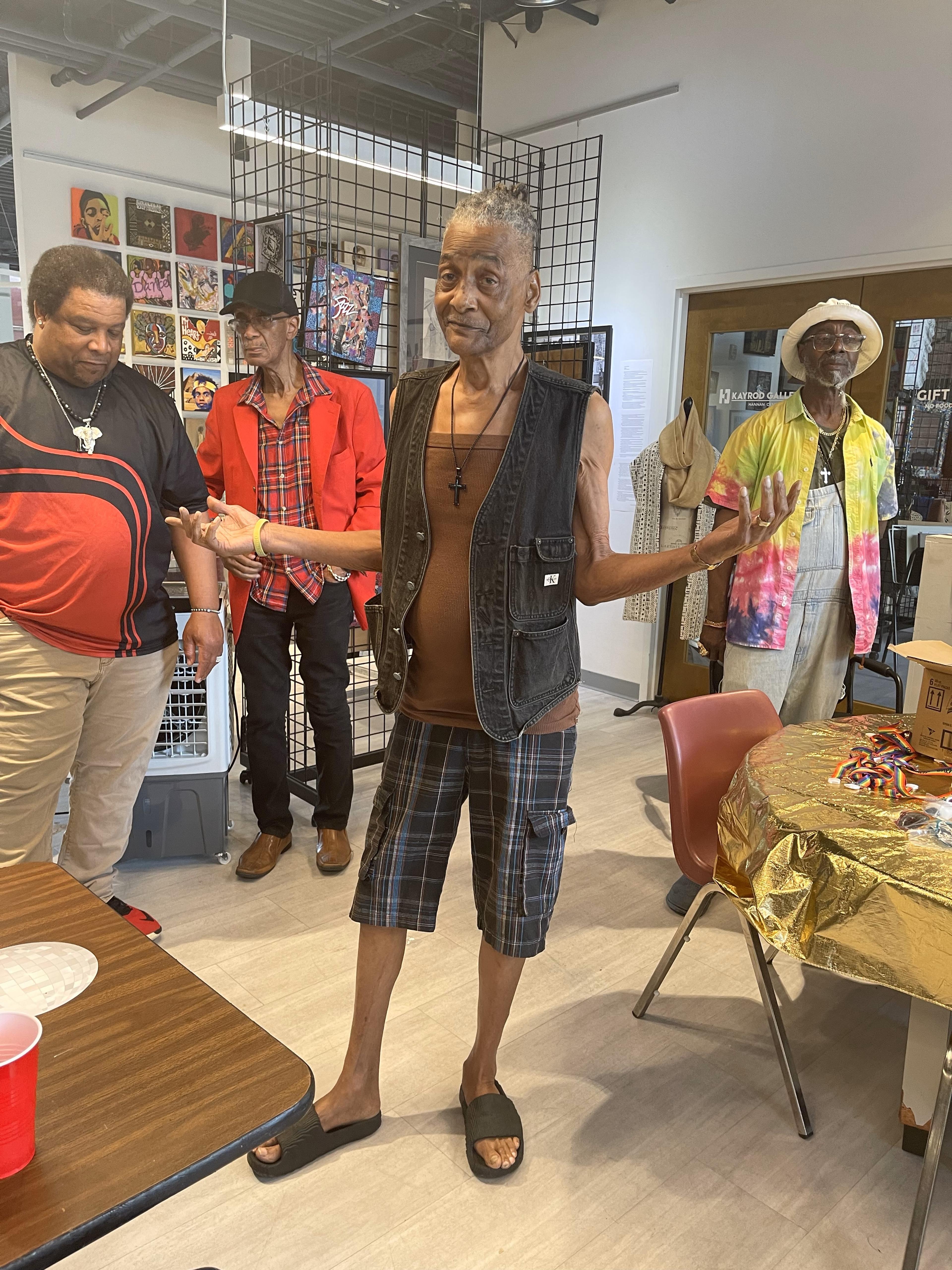

Photo credit: Melissa Draughn/Hannan Center